Microscopy is a cornerstone of biomedical research, enabling detailed study of biological structures at multiple scales. Advances in cryo-electron microscopy, high-throughput fluorescence microscopy, and whole-slide imaging allow the rapid generation of terabytes of image data, which are essential for fields such as cell biology, biomedical research, and pathology. These data span multiple scales, allowing researchers to examine atomic/molecular, subcellular/cellular, and cell/tissue-level structures with high precision. A crucial first step in microscopy analysis is interpreting and reasoning about the significance of image findings. This requires domain expertise and comprehensive knowledge of biology, normal/abnormal states, and the capabilities and limitations of microscopy techniques. Vision-language models (VLMs) offer a promising solution for large-scale biological image analysis, enhancing researchers’ efficiency, identifying new image biomarkers, and accelerating hypothesis generation and scientific discovery. However, there is a lack of standardized, diverse, and large-scale vision-language benchmarks to evaluate VLMs’ perception and cognition capabilities in biological image understanding. To address this gap, we introduce Micro-Bench, an expert-curated benchmark encompassing 22 biomedical tasks across various scientific disciplines (biology, pathology), microscopy modalities (electron, fluorescence, light), scales (subcellular, cellular, tissue), and organisms in both normal and abnormal states. We evaluate state-of-the-art biomedical, pathology, and general VLMs on

Micro-Bench and find that: i) current models struggle on all categories, even for basic tasks such as distinguishing microscopy modalities; ii) current specialist models fine-tuned on biomedical data

often perform worse than generalist models; iii) fine-tuning in specific microscopy domains can cause catastrophic forgetting, eroding prior biomedical knowledge encoded in their base model. iv) weight interpolation between fine-tuned and pre-trained models offers one solution to forgetting and improves general performance across biomedical tasks. We release Micro-Bench under a permissive license to accelerate the research and development of microscopy foundation models.

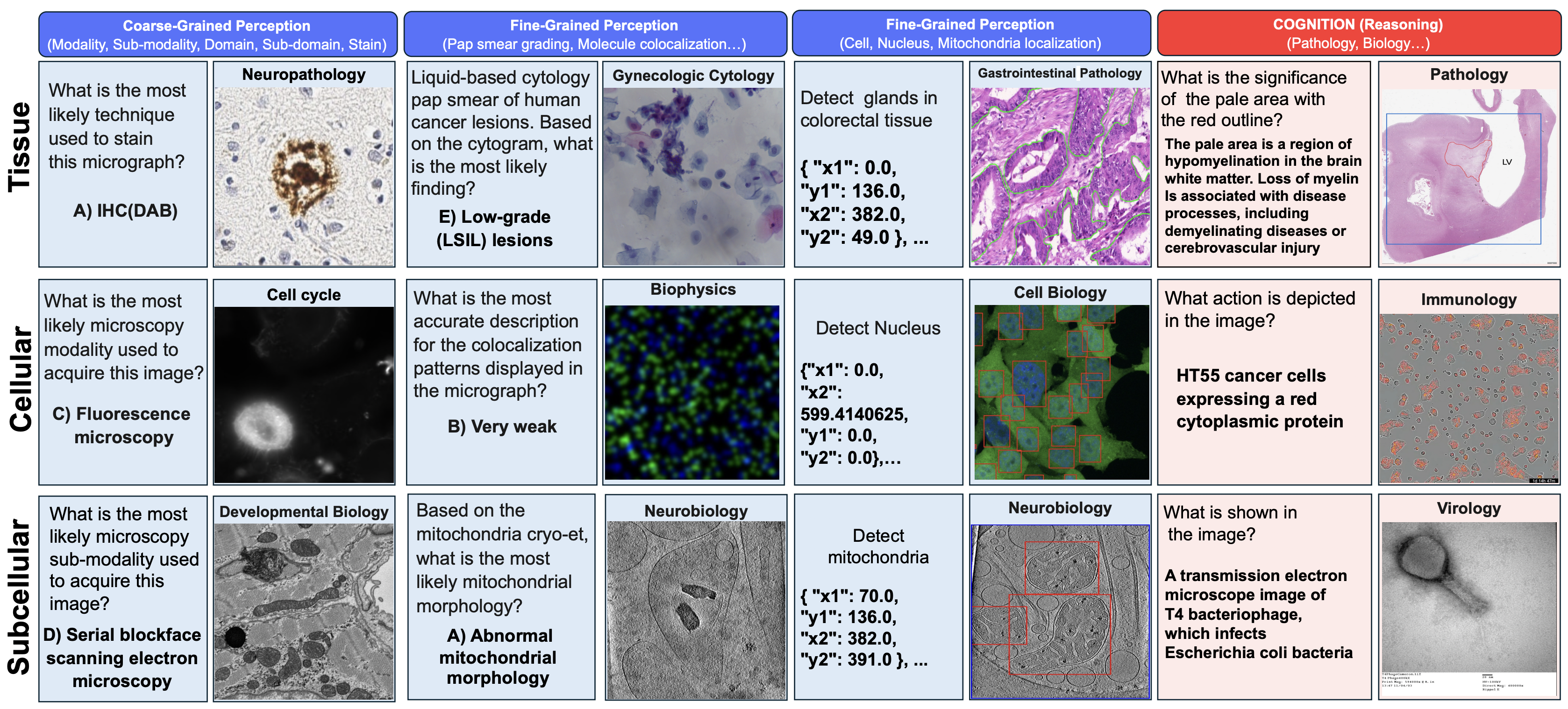

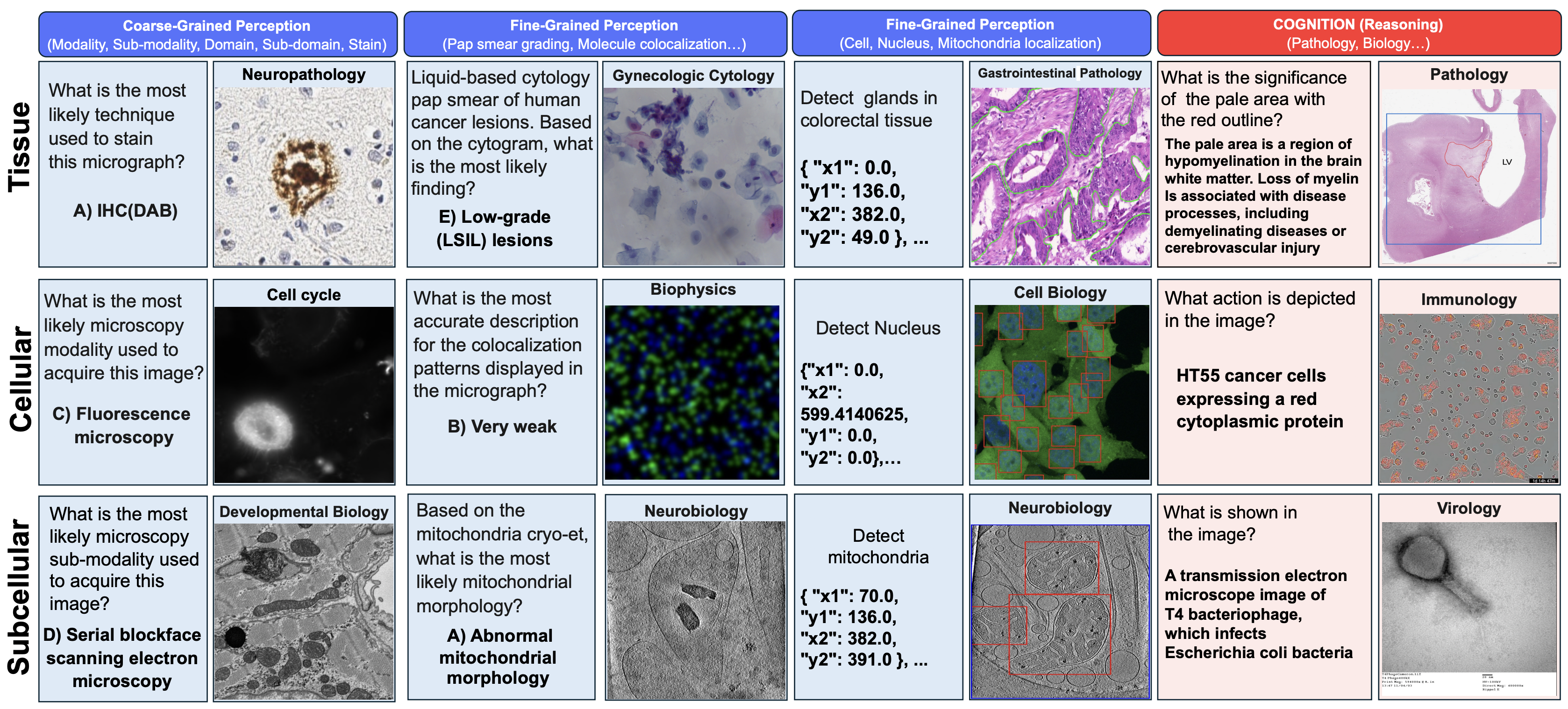

Figure 1: Data samples from Micro-Bench, covering perception (left) and cognition (right) tasks across

subcellular, cellular, and tissue levels tasks across electron, fluorescence, and light microscopy.

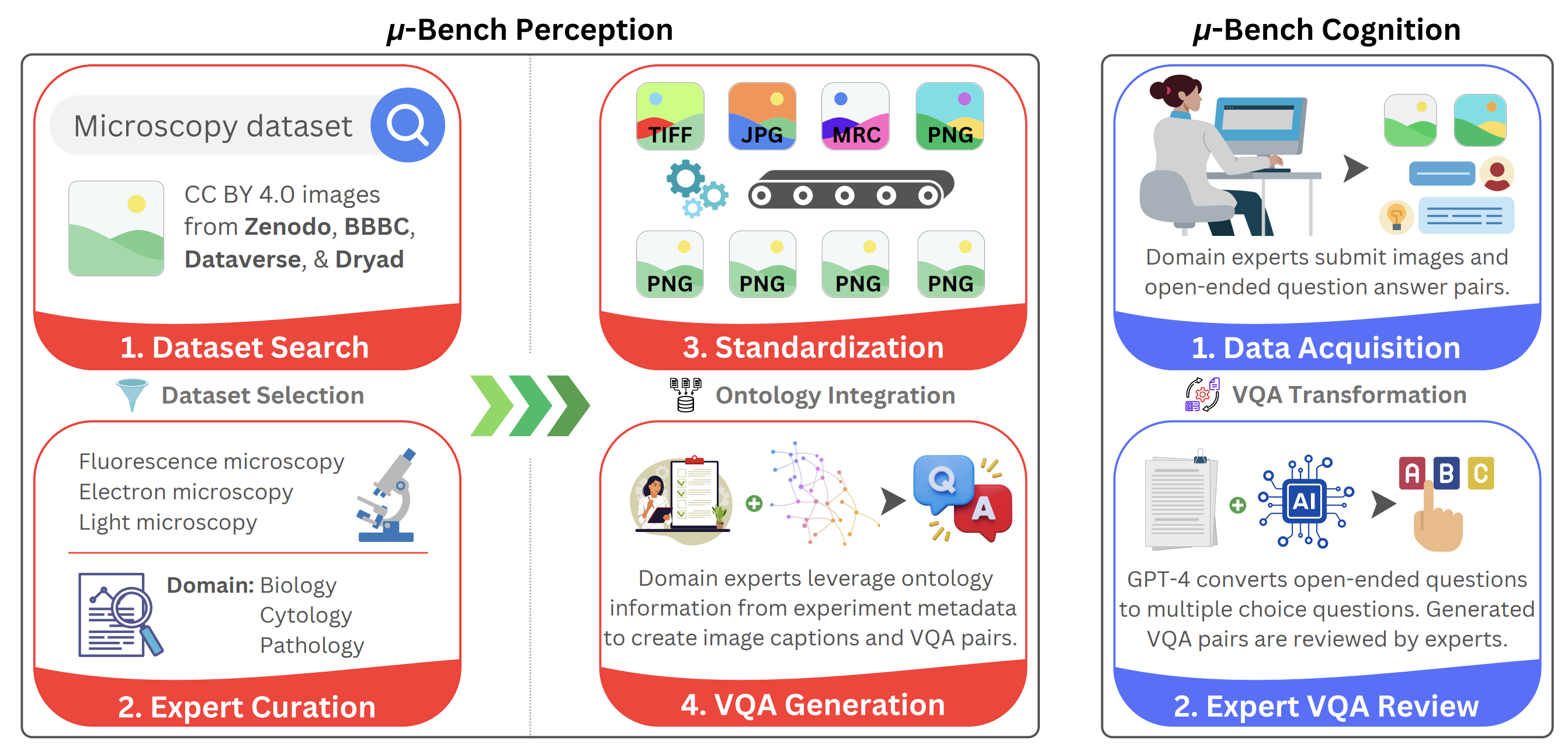

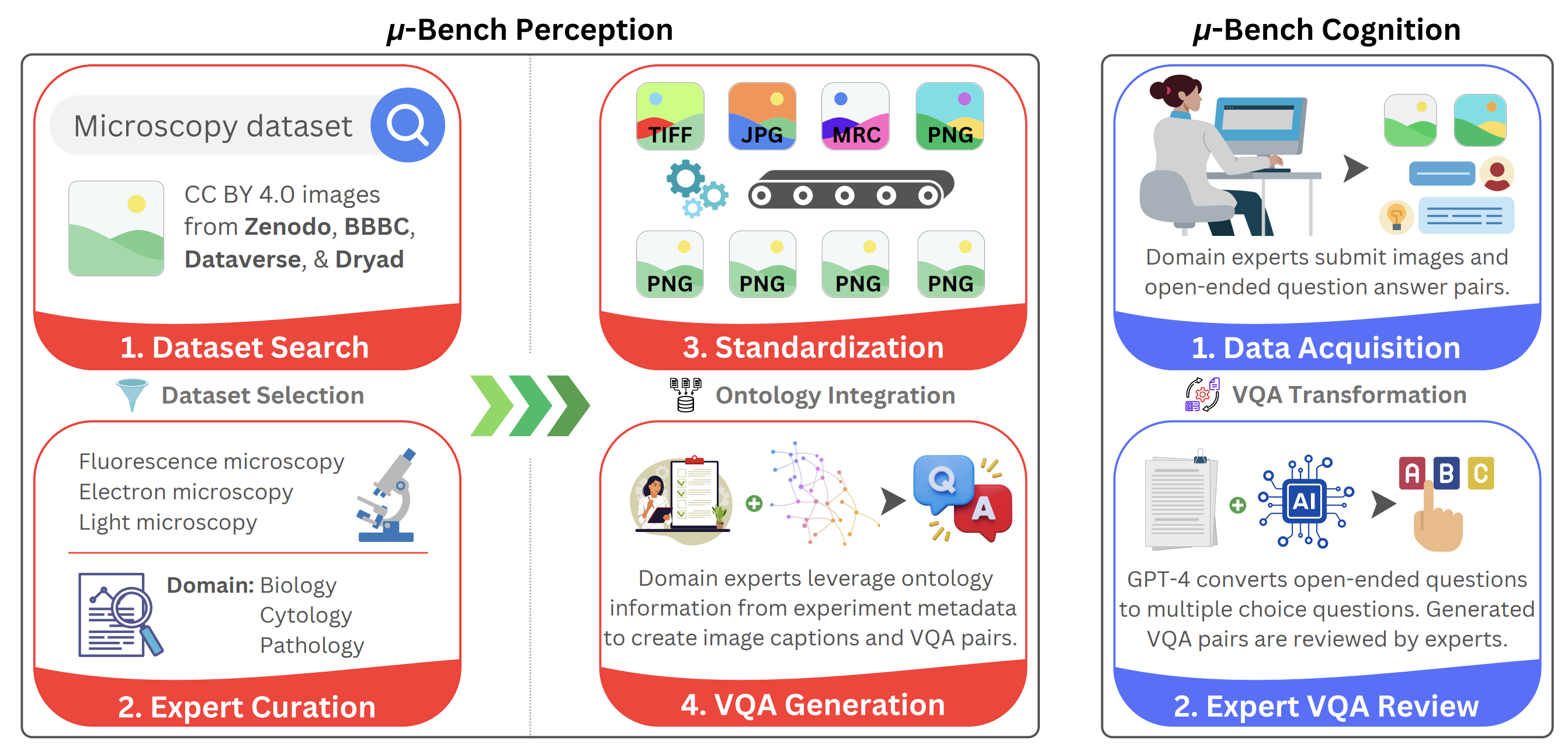

Recognizing the need for an expert-level benchmark in microscopy for comprehensive biological and biomedical understanding, we developed a benchmark to assess the perception and cognition capabilities of VLMs in microscopy image analysis following the methodology shown in Figure 2.

At a high level, the pipeline consists of two main components: (i) An biomedical expert categorized potential tasks and collected diverse microscopy datasets across multiple scientific domains, focusing on evaluating perception capabilities.

(ii) We then complement Micro-Bench by crowdsourcing questions from a larger group of microscopists using a web application.

Figure 2: Micro-Bench construction protocol. Perception dataset (left): first taxonomize use cases

across subcellular, cellular, and tissue-level applications and collect representative datasets spanning

multiple imaging modalities to test those scenarios. Next, datasets are converted to a common

format, and the ontological information extracted from their metadata is standardized. Aided by

this information, experts synthesize VQA pairs designed to test perception ability. Cognition

dataset (right): First, domain experts use an interactive web application to upload their images and

corresponding open-ended VQA pairs. Next, GPT-4 transforms the VQA pairs into a close-ended

multiple-choice format. All GPT-4 generations are reviewed by experts before being incorporated

into the cognition dataset.

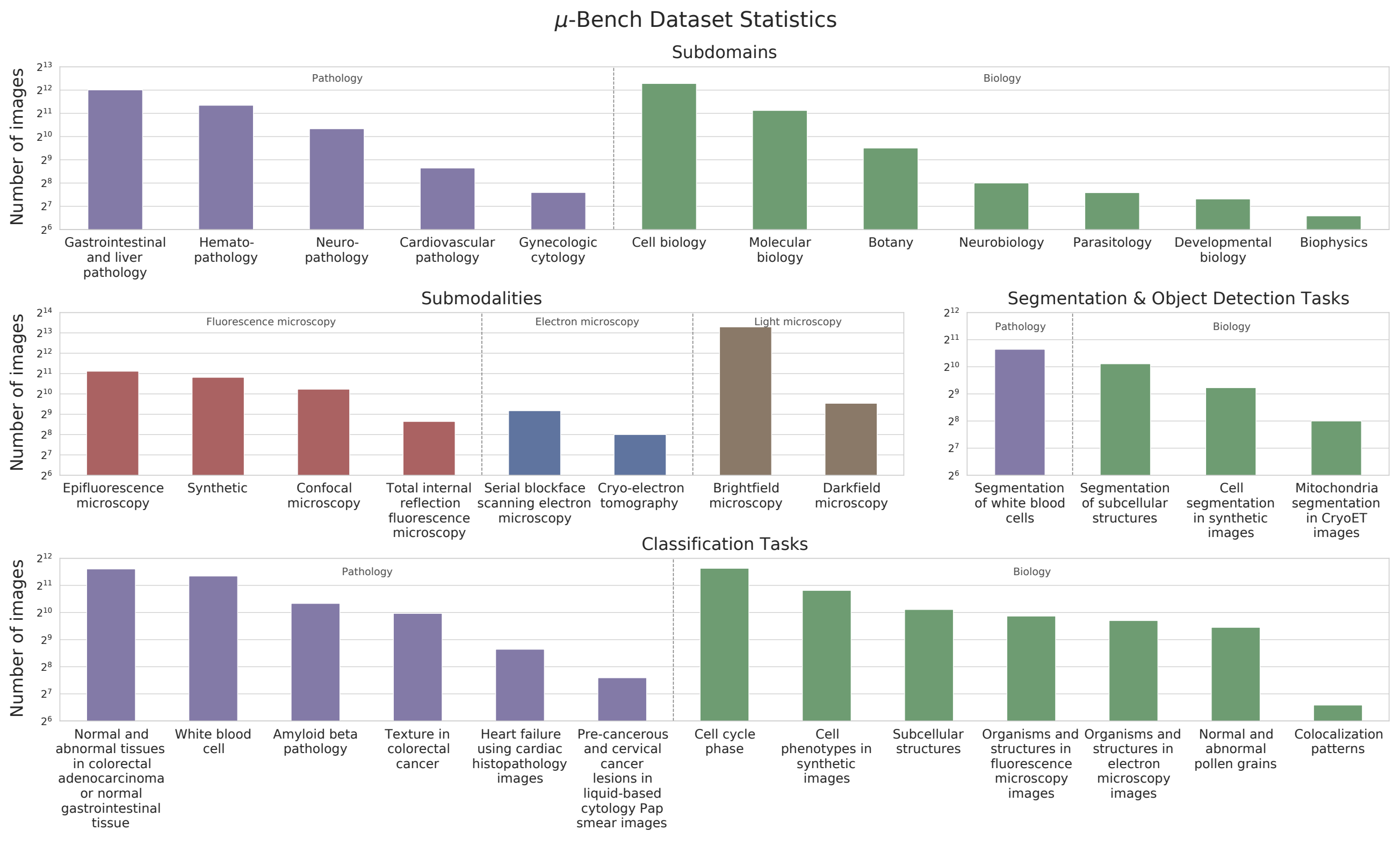

Dataset Statistics:

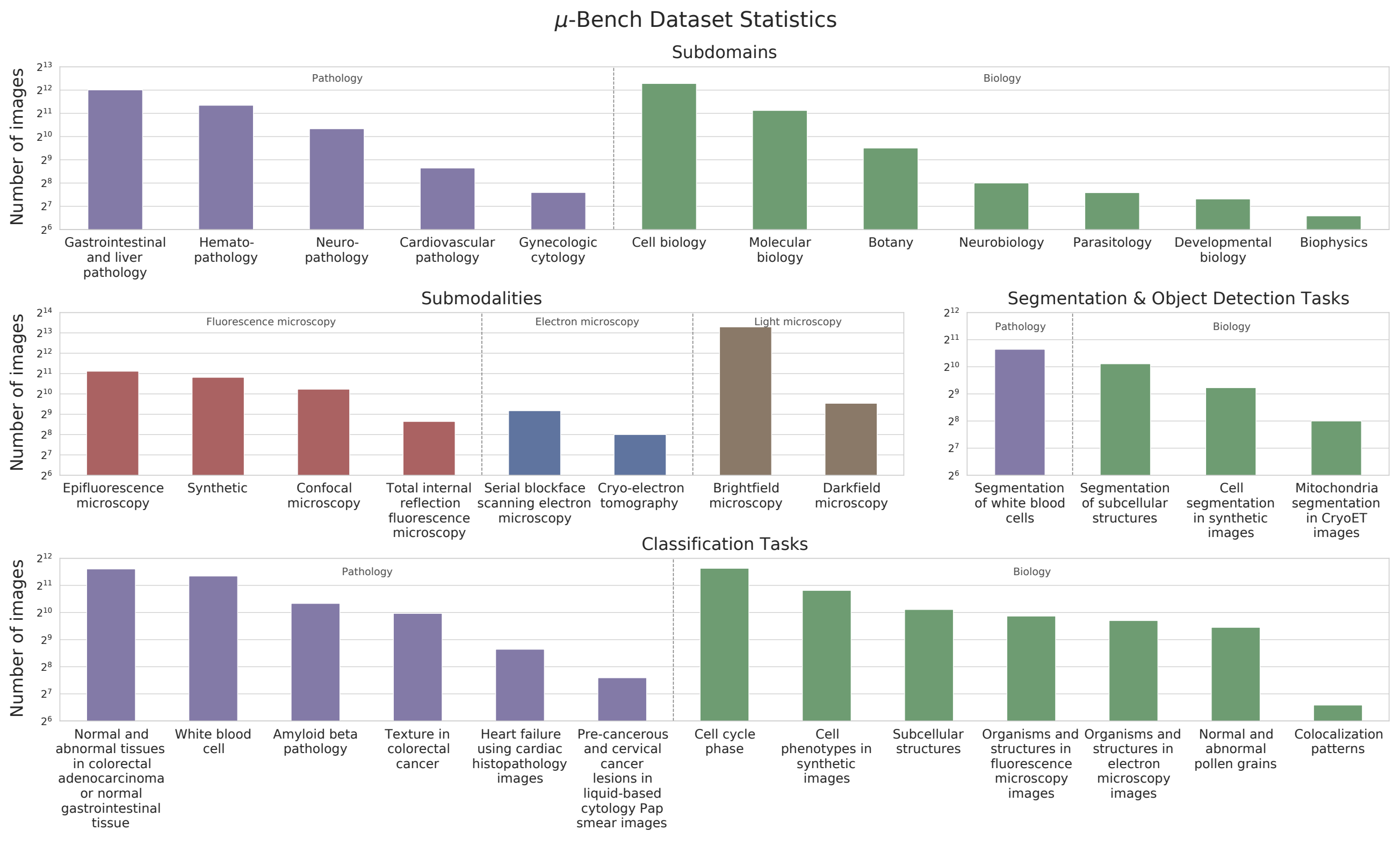

Perception Dataset Statistics: For our perception benchmark, we collected a total of 17,235 microscopy images from 24 distinct public datasets with permissive licensing, prioritizing

open CC-BY licenses. To the best of our knowledge, Micro-Bench Perception is the most diverse

microscopy vision-language benchmark, spanning light (LM), fluorescence (FM), and electron microscopy (EM), covering 8 microscopy sub-modalities (see Figure 3), 91 unique cells, tissues, and

structures over 24 unique staining techniques. The perception benchmark subset spans this diversity

through closed VQA, object detection, and segmentation.

Figure 3: Micro-Bench Perception dataset statistics. The Perception benchmark consists of microscopy

images from 12 subdomains in Biology and Pathology, obtained using 8 different imaging techniques,

including light, fluorescence, and electron microscopy. It includes 17 perception fine-grained tasks:

13 for classification and 4 for segmentation or object detection.

Cognition Dataset Statistics: For our cognition benchmark, we collected 54 microscopy images

and 121 questions from experts in the field. Entries were received from 6 users across 5 different

institutions. The Micro-Bench Cognition dataset encompasses 3 modalities (fluorescence, electron, light)

with 12 sub-modalities, 2 domains (pathology and biology) with 14 sub-domains, and 3 scales (nano,

micro, macro), covering a diverse range of topics such as pathology, immunology, and virology.

Distributions are shown in Appendix Table 14.

Benchmarking

Data artifacts like Micro-Bench enable studying model behavior within specialist domains. Since our

benchmark covers a wide range of biomedical tasks, we can, for the first time, compare biomedical

perception and cognition capabilities across microscopy imagining modalities. In this section, we

show the utility of μ-Bench by reporting empirical findings on a range of VLMs.

First, we categorized VLMs into two groups: generalist models trained on natural images and

language, and "specialist" models, fine-tuned on biomedical data. Within generalist models, we also

distinguish between contrastive and auto-regressive models.

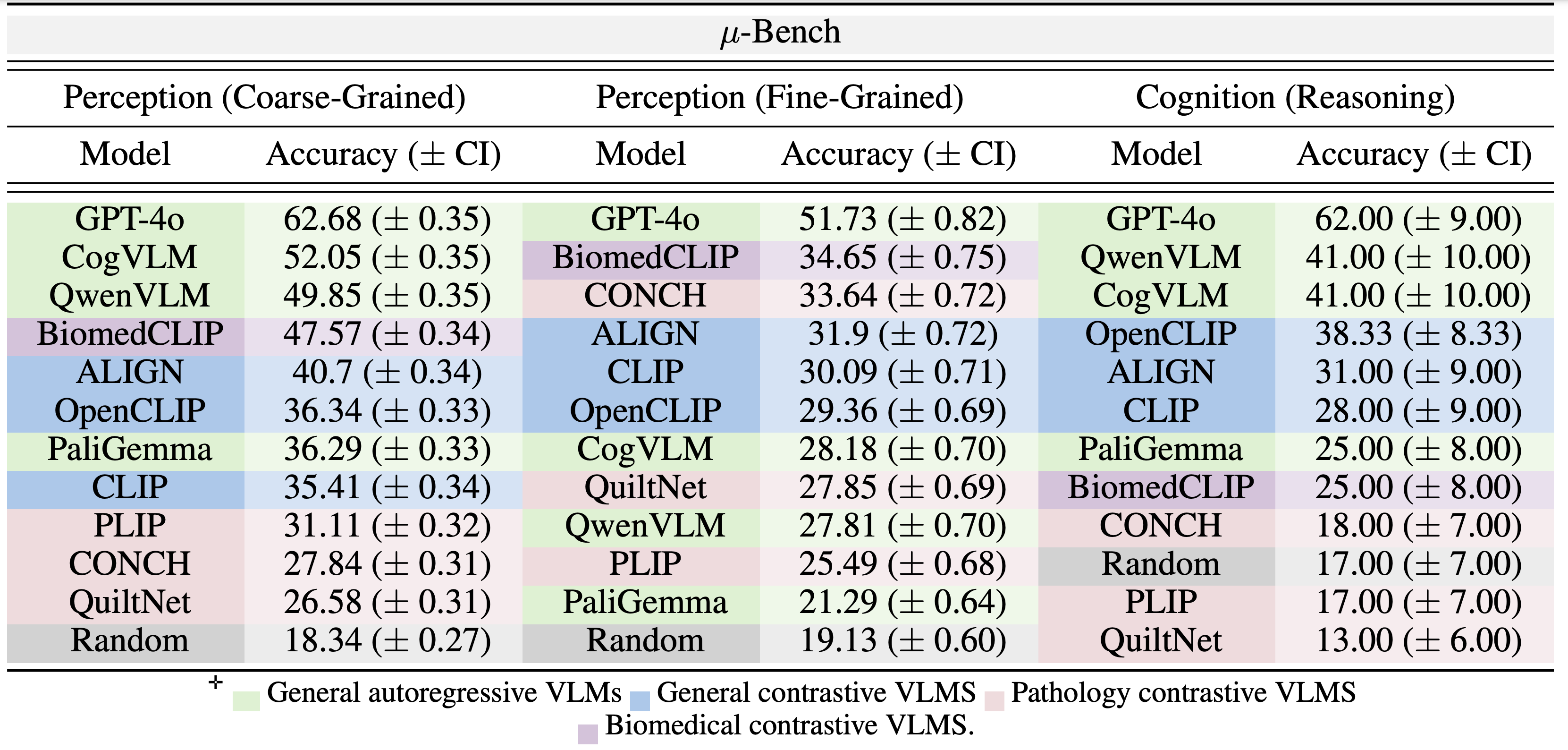

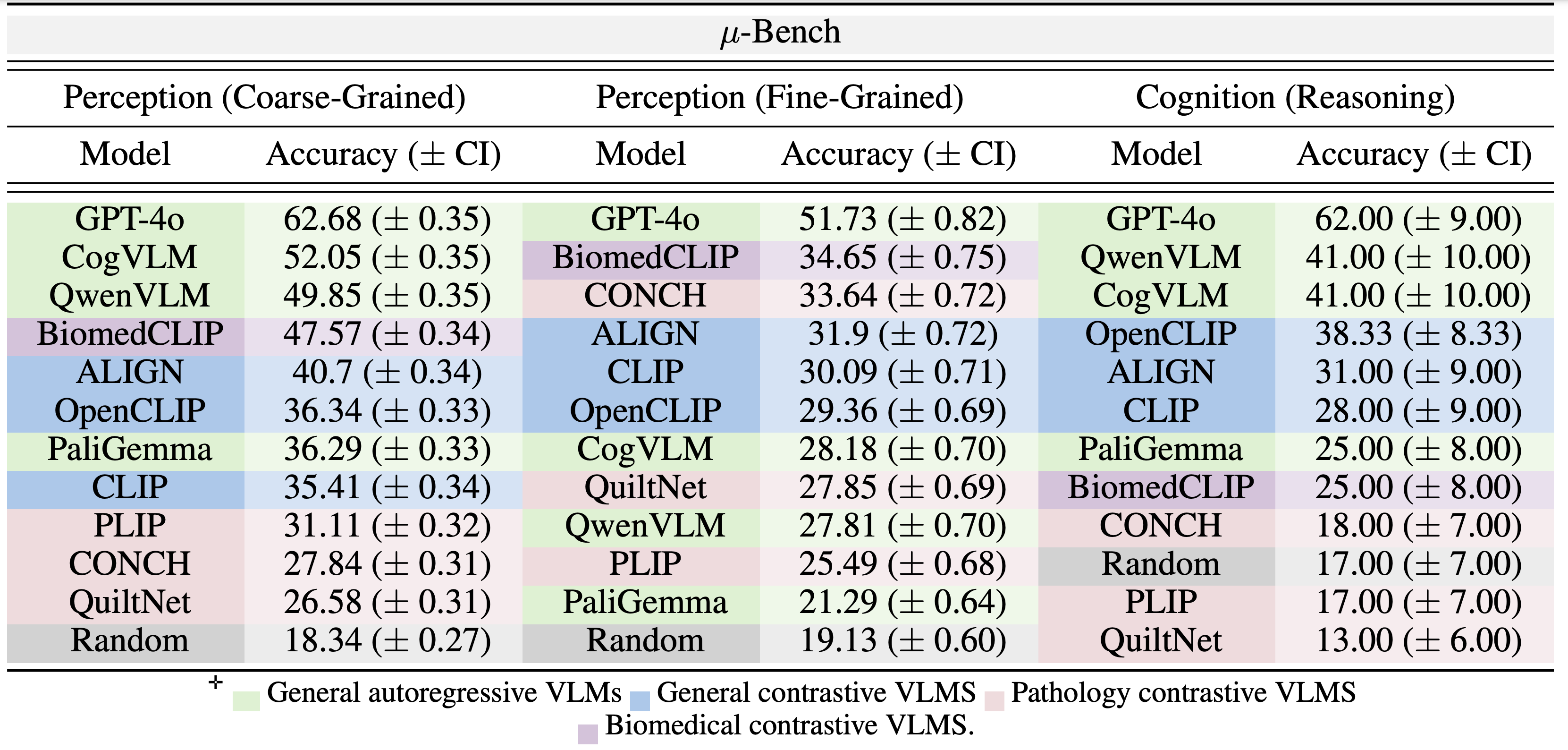

Table 1: Macro-average accuracy (with bootstrap confidence interval) for coarse-grained and fine-

grained perception and cognition (reasoning) in μ-Bench.

Findings

While specialist models are explicitly developed for the biomedical domain, they can sometimes underperform non-specialized open-

source models. For example, in both coarse-grained perception and cognition tasks (Table 1), GA

models (CogVLM and QwenVLM) outperform the best SC model (BiomedCLIP) by 4.4% and 16.0%

margins respectively. While GA models have a different training objective, larger training mixture,

and more model parameters, a similar trend is observed with GC models (ALIGN, OpenCLIP, and

CLIP) as they outperform all pathology VLMs in the same tasks by at least 9.5% (PLIP- ALIGN) and

20.3% (CONCH - OpenCLIP) respectively. This ranking is reversed in fine-grained perception tasks,

where BiomedCLIP and CONCH perform best. Indeed, fine-grained perception closely resembles

the data mixture used to fine-tune contrastive specialist models. This characterization shows

weakness in current microscopy biomedical model development.

Specialist training can cause catastrophic forgetting Base models like (OpenCLIP and CLIP) surprisingly outperform their fine-tuned counterparts (PILP and QuiltNet) in coarse-

grained perception and cognition (Table 1). Specifically, PILP and QuiltNet are fine-tuned directly

from OpenCLIP and CLIP using only pathology data closest to Micro-Bench fine-grained perception

tasks. Although it improves performance on pathology-specific fine-grained tasks, it

degrades performance (compared to their base models) on other tasks.

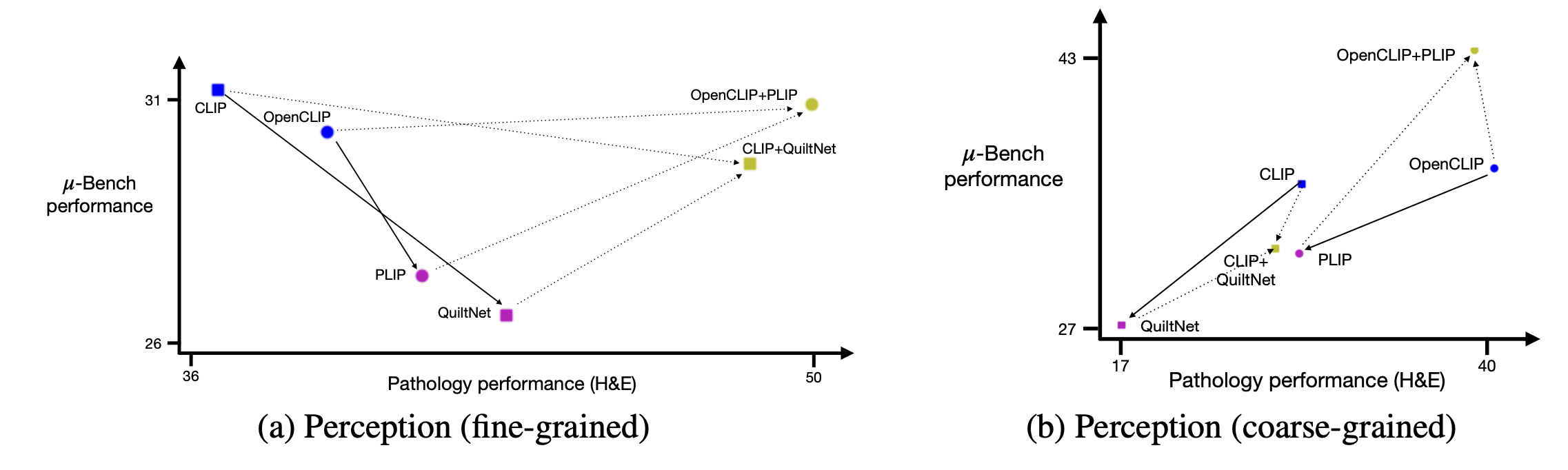

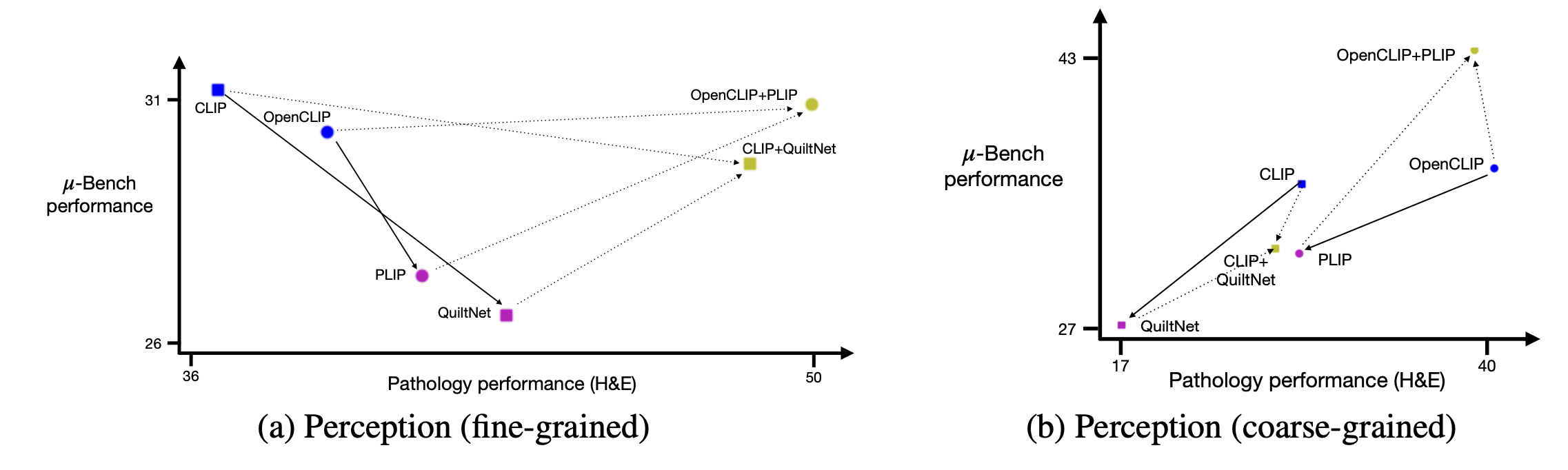

Micro-Bench characterization drives robust model development To address catastrophic forgetting

identified in our multi-level evaluation, we ensemble base model weights (OpenCLIP / CLIP) with finetuned model weights (PLIP/QuiltNet) to create merged models (PLIP+OpenCLIP / QuiltNet+CLIP),

as suggested. As shown in Figure 5, when comparing merged models to their fine-tuned

counterparts, perception performance increases across all of Micro-Bench (y-axis), including pathology-specific tasks (x-axis).

Figure 4: Fine-tuning and microscopy perception generalization on Micro-Bench . Base CLIP models

(blue) are fine-tuned to PLIP and QuiltNet using pathology data mixtures (pink). Weight-merging base

models with their corresponding fine-tuned models (olive) improves specialist zero-shot performance

on Micro-Bench coarse-grained (Left) and fined-grained (Right) perception.

Conclusion

Benchmarks drive advancements in machine learning by providing a standard to measure progress and allowing researchers to identify weaknesses in current approaches.

Thus, the lack of biomedical vision-language benchmarks limits the ability to develop and evaluate specialist VLMs. We address this gap in

microscopy by introducing the most extensive collection of vision-language tasks spanning perception

and cognition. We use Micro-Bench to establish, for the first time, the performance of some of the most

capable VLMs available and find high error rates of 30%, highlighting room for improvement. We

demonstrate how Micro-Bench can be leveraged to generate new insights. Lastly, we share Micro-Bench to

enable researchers to measure progress in microscopy foundation models.